11: Case Tracking and Program Evaluation

Case Tracking

Case tracking involves collecting data about a case. Discuss, as a team, which data elements are important for the MDT to collect by identifying the purpose of the data and how they will be used. The purpose of case tracking might include:

- Enabling the MDT to analyze their caseload

- Ensuring that cases are being monitored

- Tracking the MDT case review meeting information

- Educating the public about the program

- Creating targeted outreach campaigns

- Supporting grant proposals or funding requests

- Recruiting reluctant members or generating buy-in

Case tracking data can sometimes also be used for program evaluation activities, for example:

- Measuring the success of specific cases

- Determining the overall functioning of the team

- Improving program performance

Case tracking form. Although there are differences among MDTs, consider developing a form that captures case-level data, sometimes referred to as a case tracking form. Data tracking systems for storing such information might be as simple as Microsoft Excel file or Access database. Data points to consider collecting include:

- MDT clients’ demographic information

- Abuser’s demographic information

- Relationship between MDT client and the abuser

- Type of abuse

- Circumstances surrounding the abusive situation

- Various assessment results

- Dispositions

- Recommendations

- Services offered and if accepted

- Case outcomes

The length of case tracking can vary considerably from initial intake to some period of time after the closure of the case. The MDT will want to decide as a team how far into a case to collect data.

Collecting data. Often, data are retained in different departments and agencies and must be extracted in some fashion from various members of the MDT. Strategies for obtaining case tracking data include:

- Collecting information at each case review

- Agency-completed forms that are returned to the MDT Coordinator

- Contacting the agency directly for information (in accordance with your team’s confidentiality and information sharing protocols or MOU)

- Appointing a staff member (e.g., the victim advocate) or a volunteer to collect the information

- Some combination of these methods

Data management plan. If a case-tracking plan is adopted, the MDT will need to develop a data management plan. The plan not only increases accountability of the data, but also reduces the number of people who handle the data and thereby increase adherence to confidentiality (data) and privacy (personal identifiable information) concerns. A data management plan might address:

- Saving all information on password protected computers

- Using secure portals and virtual communication platforms, particularly if there is a hybrid team

- Using identification numbers for each person entering data

Incorporating periodic review of data forms for completeness and accuracy. Data checking can be accomplished by randomly selecting, for example, 10% of the cases. Compare the printouts of data entered with the original forms. Be sure to report the time and date of reviews and any conclusions. If problems are identified, bring these problems to the MDT to identify solutions. There are also programs for purchase that can accomplish data checking tasks.

Primer on Program Evaluation

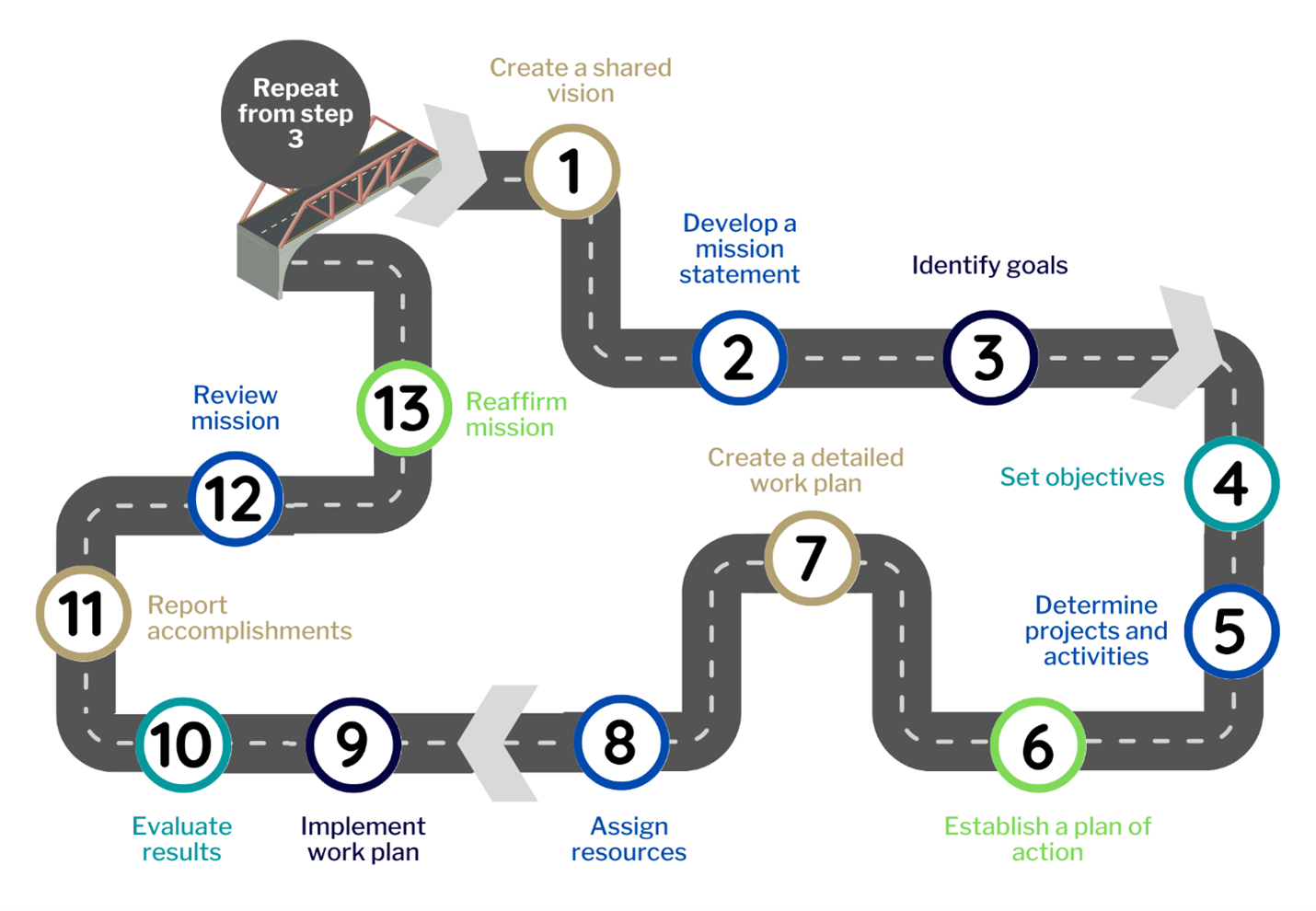

Program evaluation is the systematic application of social research procedures for assessing the conceptualization, design, implementation, and utility of social intervention programs. The focus is on a particular program to systematically produce trustworthy and credible information that is action-oriented to assist in decision making or improve a program. Program evaluation should be part of a program’s development. Below is a graphic depiction of where evaluation fits into the development of an MDT program.

This image shows a two-lane road with numbers 1 through 13 at various points along the road with the following steps by each number:

- Create a shared vision

- Develop a mission statement.

- Identify goals

- Set objectives

- Determine projects and activities

- Establish a plan of action

- Create a detailed work plan

- Assign resources

- Implement work plan

- Evaluate results

- Report accomplishments

- Review mission

- Reaffirm mission

At the end of the road, the road meets up with a bridge to the beginning of the road with a sign saying to repeat from step 3.

The Value of Program Evaluation

The value of program evaluation is not always appreciated by practitioners. Strong evaluation helps protect the integrity of the program and can be a powerful tool for program sustainability. Evaluations can be used to:

- Promote the model of service delivery to funders and other stakeholders

- Serve as the basis for making changes in program design

- Identify areas for professional development

- Determine new partners needed to strengthen the MDT

- Leverage results to obtain, retain, or expand funding

Logic Model for Program Evaluation

One of the first steps to take when developing a program is to create a logic model. A logic model is simply a visual representation that depicts and describes how a program will work. A logic model is your theory of change. The factors in the logic model form the foundation for the evaluation.

A logic model will be used throughout the life of a program and across different types of evaluation. The logic model helps ensure that you are clear from the beginning what the expected objectives and outcomes will be for the MDT and what specific changes are expected for what specific population. Below are two sample logic models.

Sample Logic Model 1

This example logic model image shows system failure leading to poor victim outcomes.

A solution is proposed which includes Trust (rules and protocols, training, communication, equal power, common vision) flowing down into Multidisciplinary Teams (MDTs) (Sharing, partnerships, interdependence, power, process).

Both Trust and MDTs then flow into Case Review (share information).

Case review (share information) then flows into Group Decision Making.

Group decision making contributes to Coordination of Investigation and Coordination of Services.

In a separate but related, model Creative and Holistic Solutions yield community benefits, victim benefits, and MDT Member benefits.

Sample Logic Model 2

This image shows six areas of a logic model.

Section 1 depicts the situation and priorities of a project.

Section 2 describes the Inputs. This is where you explain the Investment: staff, volunteers, time, money, research base, materials, equipment, technology, partners.

Section 3 describes outputs including Activities (what we do) and Participation (who we reach).

- Under activities is listed: conduct workshops and meetings, deliver services, develop products, curriculum, resources, train, provide counseling, assess, facilitate, partner, work with media.

- Under Participation is listed: participants, clients, agencies, decision-makers, customers.

Section 4 describes Outcomes – Impact. This section is divided into short-term, medium-term and long-term.

- Under short term, the following results are listed: learning, awareness, knowledge, attitudes, skills, opinions, aspiration, and motivations.

- Under medium term, the following results are listed: action, behavior, practice, decision-making, policies, and social action.

- Under long term, the following results are listed: conditions, social, economic, civic and environmental.

Section 5 relates your inputs and outputs to assumptions.

Section 6 relates your outcomes to external factors.

Program Monitoring

Evaluation (discussed next) tends to happen at key points in a program lifecycle, while program monitoring takes place throughout the life of a program. The purpose of monitoring is to track implementation progress through periodic data collection. The goal is to provide early indications of progress (or lack thereof). Use your logic model as your guide, along with case tracking data (and additional data needed for program monitoring). Compare your data to your logic model to confirm where your program is working well and to identify areas in need of attention.

For example, just prior to the Los Angeles Elder Justice Forensic Center being created, they had concluded that the MDTs that had developed in response to elder abuse cases were extremely large, and it was difficult to actively work through a case, necessitating change.

Four Primary Types of Program Evaluation

Once your logic model is completed, an evaluation plan can be developed. As presented in the graphic below, the two broad categories of evaluation include Formative Evaluation and Summative Evaluation. The difference between these two categories is the developmental stage of your program. Each of these broad categories has two types of evaluation that fall within each category, with distinct purposes. However, the four evaluation types relate to one another in that each one builds upon the other. In practice, often a program will utilize only one type of evaluation, but even if you choose to use just one type, it is useful to understand how these four evaluation types relate to one another.

This image shows five columns with an arrow running perpendicular near the top of the columns. The left side of the arrow says Formative and the right side says Summative. Under these headings it reads, “These summative evaluations build on the data collected in the earlier stages.”

Formative evaluation includes needs assessment and process/implementation evaluation. Summative evaluation includes outcome evaluation and impact evaluation.

Down the first column are three categories: Program Stage, Question Asked, and Evaluation Type.

Each of the remaining columns describes a different type of evaluation.

A needs assessment is conducted before the program begins and answers the questions, “To what extent is the need being met? What can be done to address this need?”

A process/implementation evaluation is conducted with a new program and answers the question, “Is the program operating as planned?”

An outcome evaluation is conducted when the program is established and answers the question, “Is the program achieving its objective?”

And an impact evaluation is conducted when the program is mature and answers the question, “What predicted and unpredicted impacts has the program had?”

Below is a brief synopsis of each type of evaluation, followed by a more fulsome discussion of each.

Formative Evaluation

Formative evaluation concerns learning about your program before it has been developed or while it is a new program. As a cooking analogy, formative evaluation is when the cook tastes the soup, decides something needs to be added, and changes the soup to make it better, to improve it, before serving it to guests.

The two types of evaluation that fall under formative evaluation are:

- Needs Assessment

- Needs assessment is a process for determining an organization's needs and gaps in knowledge, practices, or skills prior to initiating the program, as well as what resources are available in your community. Using the soup analogy, the question might be Have you looked at the recipe and then what you have in your house, and then developed a grocery list so you have everything you need to begin cooking?

- Process Evaluation

- Here, once the program is operational but still in the early stage of development, you are asking Is the program being implemented the way I intended? Is case review being conducted according to plan? Is the process for referral of cases to the MDT being followed? Using the soup metaphor, the question might be Is the cook actually following the recipe? If the recipe calls for 1/2 t of salt, is the cook putting in 1/2 t of salt?

Summative Evaluation

Summative evaluation is conducted after the program is well-established. In the soup analogy, summative evaluation is when the guests taste the soup. The two types of evaluation that fall under formative evaluation are:

- Outcome Evaluation

- Now you are asking Did the program achieve its desired outcomes?, which are outlined in the logic model. You might ask As a result of the MDT, what percentage of cases are services coordinated for older adults?; or As a result of the MDT, are more cases being referred for prosecution? Using the soup analogy, the question might be Did the people eating the soup like the soup; Did the soup satiate their hunger?

- Impact Evaluation

- Finally, with an impact evaluation the question is What is the difference between what happened with the program compared to what happened without the program? The added value of an impact evaluation is that it lets you assess the cause of the change and therefore impact evaluations always involve the question “compared to what?” Using the soup analogy, the question might be What impact did eating the soup have on your guest’s health compared to not eating the soup?

The material below provides additional detail for each of the four types of evaluation.

Needs Assessment

When developing a program, many communities will undertake a needs assessment. A needs assessment is the systematic effort to gather information from various sources that will help you identify the needs of clients in your community and the resources that are available to them. The needs assessment forms the foundation for program development and precedes the process evaluation.

Here is a six-step process for engaging in a needs assessment.

- Step 1. Formulate Needs Assessment Questions

- Step 2. Review Existing Data Sources

- Step 3: Collect New Data

- Step 4. Analyze Data

- Step 5. Report Findings

- Step 6. Use Your Findings

You may also utilize EJI’s Needs Assessment Planner to aid in developing and tracking your needs assessment.

Process Evaluation

A process evaluation documents the process or implementation of a program. Here you are looking for evidence of how your program has been implemented in reality, whether it is reaching the intended audience, and is producing desired outputs in comparison to your intentions. The focus is on identifying gaps for the purpose of program improvement. To later engage in an outcome evaluation, it is imperative to understand that the program is being implemented as intended and therefore a process evaluation precedes an outcome evaluation.

A process evaluation requires a deep dive into the program. Start by reviewing the activities and output components of the logic model (the “as intended” part of the process). Then take a walk through the program, mapping the program, and asking people about what they think about the program, for example, MDT member satisfaction. Note that you are not tying these activities to outcomes yet.

Some questions that could be addressed by a process evaluation include:

- Whether program activities were accomplished

- Assess the quality of program components

- How well program activities were implemented

- How external factors influenced the program

Three Areas of Inquiry

The process evaluation will involve three areas of inquiry.

1) Program Environment

Here you are describing the operating environment to enable other communities to determine whether they might achieve similar results. Factors to consider might include:

- Significant changes in the environment

- Macro-events that impact the program

2) Implementation Process

As discussed above, here you are describing the implementation process and this would involve elements such as:

- Interaction among participants (MDT members)

- The extent of participation (for example, by various agencies, units, and individuals)

- Training provided for members

- Interaction among participants and others in the community who were not involved in planning and implementing the program

3) Assessing Outputs

Here you are asking whether expected outputs were actually produced. Examples of outputs include:

- Number of cases referred to the MDT

- Number and category of case types

- Number of case review meetings

- Number and types of training provided to the MDT

- Number of joint interviews

Based on these sources of data, including interviews with key stakeholders, a set of recommendations for program improvement will emerge.

Client Satisfaction

Once your process evaluation is completed, you may want to implement a client satisfaction survey, typically an intermediary step between the process evaluation and the outcome evaluation (it is not an outcome because it does not measure the results achieved).

The challenge associated with client satisfaction surveys is that clients do not always perceive the “process” the way professionals within the systems perceive the process. While the MDT may perceive the investigation, services, and case review as a seamless process, clients may want to rate those activities individually. Client satisfaction surveys may address whether clients:

- Feel satisfied with their interactions with various team members

- Feel satisfied with the intervention

MDT Functioning and Satisfaction

At some point after the MDT has been established, you will want to evaluate the functioning and effectiveness of your MDT. You may want to focus your evaluation on the elements of a successful MDT. These characteristics will need to be quantified for evaluation purposes. For example, items addressing team trust and cohesion might include:

- The team has a shared interdisciplinary team philosophy

- The team has honest communication

- The team readily shares knowledge (as opposed to information), for example, through informal and formal cross training

- MDT members are comfortable exchanging information

- There is a sense of collegiality among MDT members

- MDT members share ideas and experiences

- There is a shared belief that working as a team leads to better client outcomes

- Mutual support is provided by MDT members

- MDT members feel trust and respect

- MDT members complement each other’s functions

- MDT members share resources

- MDT members enhance each other’s capacity to address the needs of their clients

Outcome Evaluation

Many of the elements in an outcome evaluation are reflected in the logic model. For example, the logic model links the program’s activities to the goals and objectives, and then identifies anticipated short‐ and longer‐term outcomes.

An outcome evaluation determines whether the program has met its goals and is improving outcomes for the people it serves (MDT members and clients). The terms “goals” and “objectives” and “outcomes” are often used interchangeably, but each is distinct. Goals are aspirational and define operationally how the mission of the organization is being implemented. Goals are intentionally:

- General

- Intangible

- Broad

- Abstract

- Strategic

Objectives are the specific milestones you plan to achieve in the short-term that enable attaining your goal(s). Think of objectives as the steps you will take to achieve the goal. Objectives are developed using the acronym SMART, used to describe the characteristics of objectives as used in evaluation. Objectives must be:

- Specific

- Measurable

- Achievable

- Realistic

- Timely

Outcomes are what you hope to achieve through your program when you accomplish the goal. If you consider goal versus outcome, the outcome is rooted in results rather than an aspirational aim that defines a goal. Although outcome and objective are similar, the outcome is the finish line for an objective.

Impact Evaluation

Impact evaluations are considered the gold standard of program evaluation, but they are also the most challenging to implement and typically require the expertise of an evaluation professional. An impact evaluation answers the question, What is the difference between what happened with the program compared to what happened without the program? If your objectives have been met, you can say the goals of the program have been met, but that does not necessarily mean your program caused the outcomes. To determine causality, there must be a comparison of some sort.

The two designs typically used in an impact evaluation are 1) experimental designs and 2) quasi-experimental designs.

Experimental Designs: Comparison of Treatment and Control Group using a Randomized Control Trial

In a simple experimental design, there is a treatment group and a control group. For example, the treatment group would be clients whose cases are reviewed by an MDT and the control group would be a similarly situated group of clients whose case is NOT reviewed by the MDT (their case is processed as it normally would through APS or law enforcement).

The critical element in an experimental design is random assignment. That is, any given individual has a 50/50 chance of being assigned to the treatment group or the control group. The purpose behind random assignment is that all differences between the two groups are eliminated. When the comparison between the two groups is made, e.g., the number of cases referred for prosecution, the difference between the two groups is truly due to the treatment and not to unknown factors. Random assignment is what allows you to talk about a program causing the desired change.

Quasi-Experimental: Comparison of Treatment and Comparison Group using a Naturally Occurring Setting

In a quasi-experimental design, there is a treatment group and a naturally occurring comparison group. For example, because of jurisdiction or other reasons, some clients would naturally go to an Elder Justice Forensic Center (EJFC) while other clients would naturally go to the police station (or APS). In this situation, we are not manipulating where clients are seen, rather, we are just observing naturally occurring differences.

Quasi-experimental designs are much easier to implement than designs involving random assignment. However, there are multiple factors that could account for any differences found between the two groups, reducing our confidence in causality. It may be that the area around the police station is more economically disadvantaged so if older adults seen at the EJFC fare better than those seen at a police station, it is much harder to attribute differences to the treatment (the MDT) because of these “confounding” factors (economic disadvantage) that differ between these two communities.

Research-Practitioner Partnerships

Regardless of the type of program evaluation, the best evaluations engage program staff, volunteers, clients, and other major stakeholders in the design and implementation of the evaluation. MDT staff are encouraged to consult with or partner with researchers when possible. There are several models for doing so.

Below are some suggestions for evaluators that facilitate good practitioner-researcher partnerships:

- Consult with practitioners from the beginning

- Determine what practitioners consider “valid” data (credibility)

- Evaluate the program in front of you, not the idealized program

- Minimize invasiveness

- Provide relevant feedback to all stakeholders

- Ask practitioners you are partnering with:

- What would you like to know about your program?

- If evaluation were really useful, and actually used, what would that look like?

- What would evaluation success look like to you?

Evaluation Logistics

Timing and Frequency of Administration of Surveys

Consider the timing and frequency of administering the survey(s). Evaluation administered at different points in the process will capture different experiences. For example, a client satisfaction evaluation administered immediately after the case has closed will capture different information than a client satisfaction survey administered six months after the case has closed.

The MDT will need to decide how frequently to administer various surveys. For example, an MDT survey could be administered annually, every six months, or after every meeting.

Instruments

There are a number of surveys that might be adapted for the purposes described above. However, there are no empirically validated measures of client satisfaction in the context of elder abuse MDTs. Where it is feasible, consider partnering with a university faculty member or graduate student who might create a survey instrument (using survey science) for your purposes.

Data Collection Plan

As part of your evaluation plan, a plan for collecting and storing data will need to be developed to ensure information is being captured that allows the evaluation questions to be answered. Several data collection plans exist.

Primer on Report Writing

Providing Context for Numbers

Once your evaluation data are collected, analyzed, and summarized, the data requires interpretation. What does your data mean? To interpret your data, you need to provide context. Without contextual information, it is hard to know what the statement means. Here is an example:

Program A increased referrals by 15% and Program B increased referrals by 15%.

It is clear that both programs increased by 15%, but it is unclear what that means. When context is added, as below, the meaning changes significantly.

Program A showed an increase in referrals from 35% to 50% while Program B showed an increase in referrals from 5% to 20%.

An increase from 5% to 20% arguably is a heftier lift than from 35% to 50%.

Similarly, the statement,

The Waverly Elder Justice Forensic Center served 300 older adults in the past year

could mean that the Center is serving a few or a lot of older adults in their community. Including the number of reports, in addition to the number of referrals, provides the needed context for this statement. As you can see, The Center received 5000 reports and referred 300 for review by the team is very different from The Center received 500 reports and 300 of those reports were referred to the MDT for review by the team. The context allows your reader to clearly understand what the numbers mean.

Numbers are one way to aid in interpreting your findings, but other possible points of comparison include:

- The outcomes of similar programs

- The outcomes of the same program from the previous year (or any other trend periods e.g., quarterly reports)

- The outcomes of a representative or a random sample of programs in the field

- The outcomes of special programs of interest, for example, those known to be exemplary models

- The stated goals of the program

Displaying Data

Finally, a quick word on displaying your data. There is a tendency to over-report numbers. The following is one example in which the Table in Presentation 1 shows all response category results whereas the Table in Presentation 2 shows only one response category.

| Expressed Needs of 478 Physically Disabled People | Great Need for This | Much Need | Some Need | Little Need |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation | 35% | 36% | 13% | 16% |

| Housing | 33 | 38 | 19 | 10 |

| Educational opportunities | 42 | 28 | 9 | 21 |

| Medical care | 26 | 45 | 25 | 4 |

| Employment opportunities | 58 | 13 | 6 | 23 |

| Public understanding | 47 | 22 | 15 | 16 |

| Architectural changes | 33 | 38 | 10 | 19 |

| Direct financial aid | 40 | 31 | 12 | 17 |

| Changes in insurance regulations | 29 | 39 | 16 | 16 |

| Social opportunities | 11 | 58 | 17 | 14 |

| Rank order | Great need for this |

|---|---|

| Employment opportunities | 58% |

| Public understanding | 47 |

| Educational opportunities | 42 |

| Direct financial assistance | 40 |

| Transportation | 35 |

| Housing | 33 |

| Architectural changes in buildings | 33 |

| Changes in insurance regulations | 29 |

| Medical care | 26 |

| Social opportunities | 11 |

The question may ask respondents to use a 4- or 10-point scale, but you do not have to report across all 4 or 10 responses. If you are primarily interested in Great need for this, report on those results and let your reader infer that the remaining responses were less than Great need for this. The Table in Presentation 2 is much easier for your reader to quickly grasp the meaning of the results.

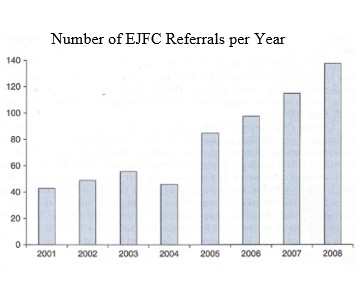

In the following example comparing a narrative to a graph, it is clear that the graph allows your reader to “at a glance” understand what your data are revealing as opposed to reading a long narrative. In report writing, brevity is your friend.

In 2001, the EJFC received 43 referrals. That number increased to 50 in 2002. The EJFC received even more cases in 2003, totaling 60. However, in 2004 the EJFC received fewer referrals (45), somewhat equivalent to 2001. The EJFC had a large increase in referrals in 2005, bumping up to 80. Each year since then, until the current year (2008), the EJFC received an additional 25 referrals in each successive year.

Utilize Evaluation Results

Utilize the information obtained from these evaluation efforts to improve your program. It may be hard to hear that all of your efforts fail to result in perfect outcomes, but keep in mind that improvement is always possible and is definitely desirable.

The value in program evaluation is widely recognized, but not everyone feels sufficiently competent to conduct their own program evaluation. Where possible, it is advisable to partner with evaluation professionals in your community willing to provide assistance. Where this is not feasible, consult this chapter for multiple helpful tips in conducting your own program evaluation.

Conclusion

While starting an elder abuse MDT presents many layers of complexity, by taking the issues one at a time, your community can develop a robust and useful team that better serves the needs of older adults who have experienced abuse. In the toolkit that accompanies this guide, there are many sample documents that you may adapt for your purposes. Additionally, the MDT Technical Assistance Center (MDT TAC) provides consultations to assist in problem solving and identifying useful resources as you develop your team. Begin by identifying a few passionate individuals who have the ability to build relationships between agencies, identify the needs of your community, lean on the insights of the various disciplines and agencies available to you, keep the focus on ways you can best serve your clients, and let the good work begin.