Plaintiff United States' Opposition to Non-Party R-CALF's and OCM's Motion for Reassignment and Consolidation

| This document is available in two formats: this web page (for browsing content) and PDF (comparable to original document formatting). To view the PDF you will need Acrobat Reader, which may be downloaded from the Adobe site. For an official signed copy, please contact the Antitrust Documents Group. |

| IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION

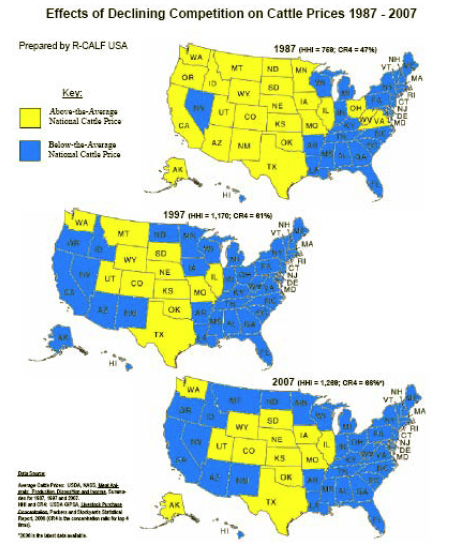

PLAINTIFF UNITED STATES' OPPOSITION TO NON-PARTY R-CALF'S AND OCM'S MOTION FOR REASSIGNMENT AND CONSOLIDATION The United States opposes the motion of Ranchers-Cattlemen Action Legal Fund, the United Stockgrowers of America ("R-CALF") and the Organization for Competitive Markets ("OCM") (collectively "R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs'") for reassignment and consolidation under Local Rule 40.4 and Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 42(a) [Docket No. 59]. The R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs seek not only to tag-along on claims the United States has alleged in this case but also to inject new grounds for finding the challenged merger illegal, based on additional facts and legal theories. R-CALF and OCM repeatedly presented these additional grounds to the United States during the course of its pre-filing investigation. But after conducting its investigation, the United States chose not to include them in its complaint. Now, the R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs seek to have their case and their private issues consolidated with the United States' case. Such an outcome is unwarranted. Courts have long recognized that the United States has a unique role in enforcing the antitrust laws and that the cases it brings in the public interest should not be encumbered or delayed by combination with suits in which private plaintiffs seek to advance their own interests. The mere presence of some common questions of law and fact does not override this strong public policy, especially where, as here, the private action relies on facts and theories not relevant to the government's case. In any event, the R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs fail to meet their burden, under the applicable rules, of demonstrating with particularity the appropriateness of reassignment and consolidation in light of the additional issues they raise. I. Background In early March 2008, JBS publicly announced that it had reached agreements to acquire National Beef Packing Company, LLC ("National") and Smithfield Beef Group, Inc. ("Smithfield") and that, through Smithfield, it would acquire ownership of Five Rivers Cattle Feeding, LLC ("Five Rivers"). The Department of Justice ("Department") proceeded to investigate whether JBS's acquisitions of National, Smithfield, and Five Rivers would likely lessen competition in violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. § 18. During the course of its investigation, the Department obtained information from numerous parties, including R-CALF and OCM.(1) These two groups repeatedly expressed concern that vertical integration by packers – that is, packers having an ownership or contractual interest in cattle before they are slaughtered (or, using R-CALF's and OCM's phrase, controlling "captive supplies") – has largely diminished the number of cattle sold on the open market and, concurrently, has enhanced packer market power in their purchase of cattle.(2) R-CALF claimed that JBS's acquisition of Five Rivers, a large feedlot operator with extensive operations throughout the United States,(3) would increase packer ownership of cattle and "exacerbate the ongoing exercise of market power." Letter from Bill Bullard, CEO, R-CALF, to Thomas Barnett, Assistant Attorney General, Antitrust Division, U.S. Dep't of Justice, at 21-22 (Apr. 9, 2008) (Ex. A). R-CALF asked the United States to block both the National and Smithfield acquisitions, including the acquisition of Five Rivers. Id. at 1-2. On October 20, 2008, the United States and thirteen states(4) filed a complaint [Docket No. 1] alleging that JBS's proposed acquisition of National will likely lessen competition in the purchase of fed cattle and in the sale of USDA-graded boxed beef to consumers in violation of Section 7. The complaint alleges that the proposed transaction would eliminate head-to-head competition between JBS and National and would make interdependent or coordinated conduct among JBS and the other two significant packers more likely. See, e.g., United States' Complaint ¶ 6. On the same day the United States filed its complaint, it also notified JBS that it would not seek to block JBS's acquisition of Smithfield. JBS has closed that acquisition and now owns Smithfield and Five Rivers. On November 13, 2008, the R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs filed their own complaint. In a press release announcing their case, they "applauded" the United States' suit to block the National acquisition but were "disappointed" that Smithfield and Five Rivers were excluded from that suit. After noting that they had encouraged the United States "to take enforcement action" against JBS's acquisition of Smithfield and Five Rivers, the R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs stated that their action would expand the United States' suit by addressing merger effects relating to Five Rivers as well as "how packers use captive supplies to leverage down prices and how this negatively impacts the price for all classes of cattle." "Cattle Producers and OCM File Suit Against JBS Merger" (R-CALF USA media release, Nov. 14, 2008) (Ex. D). Although much of their complaint is lifted verbatim from the United States' complaint, the R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs make additional factual allegations about Five Rivers (e.g., ¶¶ 3 & 12) and the likely effects arising from vertical integration and captive supply issues (e.g., ¶¶ 28 & 29) that are not present in the United States' complaint. The R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs also allege specifically that JBS's acquisition of National violates Section 7 of the Clayton Act based on the "increased concentration in feedlot ownership" and the "increased reliance on captive supplies." ¶ 48(d). Those theories of liability are not in the United States' complaint. The R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs nonetheless now seek to have their case reassigned and consolidated with the United States' action. II. Argument Whether to reassign a case under Local Rule 40.4 and consolidate it with another action pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 42 lies within the sound discretion of this Court. King v. Gen. Elec. Co., 960 F.2d 617, 626 (7th Cir. 1992) ("A district court's decision to consolidate cases is subject to review only for an abuse of discretion."); Clark v. Ins. Car Rentals, Inc., 42 F. Supp. 2d 846, 847 (N.D. Ill. 1999). Here, consolidation is unwarranted given the strong public policy against combining private actions with public antitrust cases and the failure of the R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs to justify reassignment and consolidation, given the additional facts and theories they seek to pursue.(5)

The United States has responsibility to represent the public interest in enforcing the nation's antitrust laws, and it should have the ability to do so without interference by private parties. See, e.g., Sam Fox Publ'g Co. v. United States, 366 U.S. 683, 693 (1961) (emphasizing "the unquestionably sound policy of not permitting private antitrust plaintiffs to press their claims against alleged violators in the same suit as the Government"). Courts have consistently held in a wide variety of procedural contexts that claims by private plaintiffs should not be combined with antitrust enforcement actions brought by the United States, especially where, as here, the United States objects to their inclusion.(6) See, e.g., United States v. Dentsply Int'l, Inc., 190 F.R.D. 140, 144-45 (D. Del. 1999) (denying consolidation of pre-trial proceedings of two "tag-along" private antitrust damages actions with antitrust enforcement action brought by the United States);(7) United States v. Visa U.S.A., Inc., No. 98 Civ. 7076, 2000 WL 1174930 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 18, 2000) (denying private party's motion to intervene during course of civil antitrust case brought by the United States); Sam Fox Publ'g, 366 U.S. at 693 (denying private party's motion to intervene for purposes of modifying antitrust consent decree obtained by the United States); see also United States v. Int'l Bus. Mach. Corp., 62 F.R.D. 530, 532 n.1 (S.D.N.Y. 1974) ("It is a firmly established general principle that a private party will not be permitted to intervene in government antitrust litigation."); 7C Wright et al., Federal Practice and Procedure § 1909, at 414 (3d. ed. 2007) ("[I]n the absence of a very compelling showing to the contrary, it will be assumed that the United States adequately represents the public interest in antitrust suits.") (collecting cases). The individual interests advanced by private plaintiffs – whether they be customers, suppliers, or competitors of the defendants in an antitrust action – will of necessity diverge from the public interest and will likely distract, delay and complicate the government's case.(8) Here, if consolidation is granted, the R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs will inject their additional theories – already rejected by the United States – into the United States' case, pursuing their private interests and complicating the litigation with new facts and legal issues. In addition, if the R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs are allowed to join this case, then other non-parties who have an interest in this industry – or even in the general enforcement of the antitrust laws – could also seek to join, resulting in enormous complexities in this case, as well as adversely affecting future government cases.(9)

The R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs have failed to establish how reassignment and consolidation is warranted given the additional facts and theories at issue in their case. Local Rule 40.4(b) sets forth the "stringent criteria," Goldhamer v. Nagode, No. 07 C 5286, 2007 WL 4548228, at *3 (N.D. Ill. Dec. 20, 2007), that the movant must meet for reassignment of a related(10) case: (1) both cases are pending in this Court; (2) the handling of both cases by the same judge is likely to result in a substantial saving of judicial time and effort; (3) the earlier case has not progressed to the point where designating a later filed case as related would be likely to delay the proceedings in the earlier case substantially; and (4) the cases are susceptible of disposition in a single proceeding. The R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs fail to meet this burden because they ignore the differences in their case and the United States' case and fail to explain how those differences would affect the current, pending matter.(11) Instead, they gloss over the issues at the crux of their motion with the conclusory statement that there are "significant similarities between the two cases." R-CALF/OCM Mem. at 5. Such a statement is plainly insufficient because the moving party must "sufficiently apply the facts of the case" to be consolidated to each element of the rule. Mach. Movers v. Joseph/Anthony, Inc., No. 03 C 8707, 2004 WL 1631646, at *3 (N.D. Ill. July 16, 2004).(12) R-CALF/OCM's memorandum fails to disclose – let alone analyze the implications of – the significant differences between the two complaints. As explained above, the R-CALF/OCM complaint contains new factual allegations concerning Five Rivers and captive supply issues and a separate legal basis for relief relating to vertical effects arising from feedlot ownership. These facts and theories are not part of the United States' case, which is grounded on horizontal claims. Proof of these facts and theories will require a significantly different evidentiary and economic basis than what will be at issue in the United States' action.(13) If consolidated, the R-CALF/OCM claims necessarily will complicate the United States' action. First, R-CALF/OCM's pursuit of a legal theory intentionally excluded from the United States' case raises the question of whether the two cases are, in fact, susceptible of disposition in a single proceeding, and the R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs have not explained how they can be. Second, introducing R-CALF/OCM and their additional issues to the United States' case would needlessly complicate the proceedings. The United States would need to account for R-CALF/OCM counsel when scheduling and taking depositions.(14) It would also need to cover additional depositions noticed by R-CALF/OCM, thereby requiring the United States to expend resources to cover depositions that it had not planned on taking on issues irrelevant to its case. The defendants also would likely seek discovery and engage in motions practice relating to issues such as R-CALF's and OCM's standing to bring their suit. Non-party witnesses would be likely to object to disclosing proprietary information to market participants and industry observers (such as R-CALF and OCM). Similarly, the R-CALF/OCM issues would likely lead to additional expert reports, pre-trial hearings and fact and expert witnesses at trial, all of which has the potential to significantly complicate the United States' action. The R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs' professed willingness to abide by the Court's discovery schedule here does not eliminate these potential disputes and additional complications, and "there is no way to ensure ahead of time that delay will not occur." Dentsply, 190 F.R.D. at 146. In short, R-CALF/OCM have failed to show that reassignment is warranted given the additional facts, theories and claims that R-CALF/OCM now seek to inject into the proceedings.(15) These concerns are equally apposite in the context of consolidation.(16) The R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs appear to argue that their case should be consolidated with the United States' action because R-CALF and OCM expended significant time and effort "urging the DOJ to rigorously investigate the potential anticompetitive impact" of JBS's proposed acquisitions and because they will help rather than hinder the government's case. R-CALF/OCM Mem. at 2-3. These claims do not warrant what is effectively intervention into a government enforcement action – over the United States' opposition – and do not distinguish the R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs from many other parties that advocate their interests before the Department of Justice. III. Conclusion For the reasons stated above, the United States respectfully requests that the Court deny R-CALF/OCM's motion to reassign and consolidate. In addition, if the Court considers arguments in the movant's reply brief that should have been made initially, the United States respectfully asks for an opportunity to rebut those untimely new arguments with oral argument.

Dated: November 26, 2008 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE Claude F. Scott, Jr., an attorney, hereby certifies that on November 26, 2008, he caused true and correct copies of the foregoing "Plaintiff United States' Opposition to Non-Party R-CALF's and OCM's Motion for Reassignment and Consolidation" to be served via the Court's ECF system on the following counsel of record in this matter:

Claude F. Scott, Jr. further certifies that on November 26, 2008, he caused true and correct copies of the foregoing "Plaintiff United States' Opposition to Non-Party R-CALF's and OCM's Motion for Reassignment and Consolidation" to be served via e-mail and first class mail on the following counsel:

FOOTNOTES 1. R-CALF submitted written materials and data to the Department on March 12, 2008; April 9, 2008; April 24, 2008; May 8, 2008; May 20, 2008; May 28, 2008; and August 1, 2008 and made in-person presentations to legal staff on April 16, 2008 and September 5, 2008. OCM met with the Department on March 26, 2008 and September 10, 2008. 2. E.g., Presentation from R-CALF to Antitrust Division Staff, at 23 (Sept. 5, 2008) (Ex. B) (highlighting how transactions would increase the "volume of captive supply cattle controlled by JBS/Swift); Letter from Bill Bullard, CEO, R-CALF, to Thomas Barnett, Assistant Attorney General, Antitrust Division, U.S. Dep't of Justice, at 11-12 (May 8, 2008) (Ex. C) (alleging that JBS ownership of Five Rivers would increase the percentage of packer-owned cattle and "thin the cash market"); Letter from Bullard to Barnett, at 14-15 (Apr. 9, 2008) (Ex. A) (alleging harm from "vertical coordination between the live cattle industry and the beef manufacturing industry" and the "present use of captive supplies"). 3. Feedlots take cattle that have reached an appropriate age and feed them a high-energy grain diet for three to six months or more. When the cattle reach an appropriate weight, they are sent to packing plants (operated by firms such as JBS or National) for slaughter and processing. 4. An Amended Complaint [Docket No. 48], filed on November 7, 2008, added four additional Plaintiff States. Each Plaintiff State brings this action in its sovereign capacity and as parens patriae on behalf of the citizens, general welfare and economy of each of their states. As such, their goals are similar to those of the United States in representing the public interest. 5. Though consolidation is inappropriate, as an alternative, the United States would not oppose the R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs making an amicus submission at the close of trial to present their views, based on the record evidence, as to the competitive effects of the transaction. See United States v. Visa U.S.A., Inc., No. 98 Civ. 7076, 2000 WL 1174930, at *2 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 18, 2000) (denying motion to intervene but granting permission to proposed intervenor to file amicus brief). 6. The case cited by the R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs, Community Publishers, Inc. v. Donrey Corp., 892 F. Supp. 1146 (W.D. Ark. 1995), is inapposite because it was the United States that moved for consolidation of its case with a previously filed private action challenging a consummated merger. Such consolidation was in the public interest and did not add additional issues to the pending private action. As the court in Dentsply observed, there is not a per se ban on consolidation of a Government antitrust case under Rule 42(a), but when the government objects, the public policy concerns outweigh other considerations in favor of consolidation. United States v. Dentsply Int'l, Inc., 190 F.R.D. 140, 145 (D. Del. 1999). 7. In Dentsply, the district court declined to consolidate cases that presented similar factual and legal issues, finding that "Congress has articulated a strong public policy against combining antitrust complaints brought by the Government with private antitrust damages suits." 190 F.R.D. at 144. R-CALF/OCM seeks to distinguish Dentsply on the basis that it involved private damages suits. R-CALF/OCM Mem. at 8-9. The Dentsply court, however, was concerned with delay that would be caused by interjecting private interests into a public action, 190 F.R.D. at 144-45, and such delay will arise regardless of whether the private suit is one seeking damages or one seeking injunctive relief on a basis advanced solely by a private party. 8. The risk of such complications outweigh any inefficiencies or burdens on the private parties that might result from a failure to consolidate. See Dentsply, 190 F.R.D. at 144-45 (recognizing public interest in expedited resolution of government antitrust actions outweighs potential burdens of duplicative discovery on defendants) (citing H.R. Rep. No. 90-1130, at 8 (1968), reprinted in 1968 U.S.C.C.A.N. 1898, 1905); Visa, 2000 WL 1174930, at *2 (denying intervention because potential delay "clearly outweighs any benefit that may accrue therefrom") (internal quotation marks omitted). 9. If other parties followed R-CALF/OCM's model – waiting until the government challenges a transaction and then seeking consolidation after filing a lawsuit that copies much of the government's complaint – the government's enforcement actions would be quickly bogged down with private plaintiffs. See Dentsply, 190 F.R.D. at 144 ("If consolidation were permitted with the Government antitrust case under Rule 42(a), it would encourage more private tag-along suits, which would likely delay future Government antitrust cases."). 10. The R-CALF/OCM case likely meets the test for a "related" case in that it involves "some of the same issues of fact or law" as the United States' case. See Local Rule 40.4(a)(2). 11. The movants satisfy only the first 40.4(b) factor: They filed their action in this Court. 12. The R-CALF/OCM plaintiffs may attempt to meet their burden by providing specific facts in their reply brief; however, arguments raised for the first time in a reply brief that should have been made in support of a motion should be deemed waived. Wells v. Bartley, 553 F. Supp. 2d 1019, 1028 n.9 (N.D. Ill. 2008) (Bucklo, J.); see also Global Patent Holdings, LLC v. Green Bay Packers, Inc., No. 00 C 4623, 2008 WL 1848142 (N.D. Ill. Apr. 23, 2008) (motion to reassign) ("We emphatically do not endorse a practice of filing underdeveloped motions or saving the bulk of a party's arguments for presentation in a reply brief."). 13. Effects arising from vertical integration raise separate analytical issues than those relating to the merger of horizontal competitors. Compare Phillip E. Areeda & Herbert Hovenkamp, Antritrust Law 900-990 (2d ed. 2006) (discussing principles for evaluating horizontal mergers), and U.S. Dep't of Justice & Fed. Trade Comm'n, Horizontal Merger Guidelines (1992) (same), with Areeda, Antritrust Law 1000-1041 (discussing principles for evaluating mergers raising vertical issues), and U.S. Dep't of Justice & Fed. Trade Comm'n, Non-Horizontal Merger Guidelines (1984) (same). 14. Under the scheduling order negotiated between the United States and counsel for JBS and National, each party is entitled to take only 35 total depositions. That number was negotiated with regard to the claims in the United States' complaint and to likely defenses, not to the claims that R-CALF/OCM now raise. 15. See generally Goldhamer, 2007 WL 4548228, at *2 (movant failed to meet second, third and fourth prongs of Local Rule 40.4(b) given that second case raised new facts and claims that will "require different discovery and motions, and will generally raise different legal issues"); Williams v. Walsh Constr., No. 05 C 6807, 2007 WL 178309, at *2 (N.D. Ill. Jan. 16, 2007) (savings in judicial time and effort must be substantial; "if the cases will require different discovery, legal findings, defenses or summary judgment motions, it is unlikely that reassignment will result in a substantial judicial savings"). 16. See Goldhamer, 2007 WL 4548228, at *2 ("In exercising our discretion on the issue of consolidation and reassignment, we look to the Local Rules for guidance."); see generally Fed R. Civ. P. 42(a) (noting unnecessary costs and delay as factors in decisions relating to consolidation); 9A Wright, Federal Practice § 2383, at 36 (3d. ed. 2008) (stating that the court must weigh any inconvenience, delay, or expense that consolidation would cause); Cf. Visa, 2000 WL 1174930, at *2 (intervention by private party would "'unduly delay or prejudice the adjudication of the rights of the original parties,' . . . by imposing additional and unnecessary burdens - in the form of new discovery, evidence, and even legal issues – on the resolution of the matter before me.") (internal citation omitted). EXHIBIT LIST

April 9, 2008 The Honorable Thomas Barnett

Dear Mr. Barnett: The Ranchers Cattlemen Action Legal Fund United Stockgrowers of America ("R-CALF USA") respectfully requests that the U.S. Department of Justice ("DOJ") carefully consider the important factors discussed below concerning the current state of the U.S. live cattle industry during the Agency's analysis of the proposed mergers by JBS Acquisitions (hereafter "JBS-Brazil") to purchase National Beef Packing Co. ("National"), Smithfield Beef Group ("Smithfield"), and Five Rivers Ranch Cattle Feeding, LLC ("Five Rivers"), (collectively "JBS-Brazil Merger"). R-CALF USA represents thousands of U.S. cattle producers on domestic and international trade and marketing issues. R-CALF USA, a national, non-profit organization, is dedicated to ensuring the continued profitability and viability of the U.S. cattle industry. R-CALF USA's membership consists primarily of cow-calf operators, cattle backgrounders, and feedlot owners. Its members are located in 47 states, and the organization has approximately 60 local and state association affiliates, from both cattle and farm organizations. Various main street businesses are associate members of R-CALF USA. R-CALF USA previously submitted a letter to your agency on March 12, 2008 expressing its initial concerns regarding the JBS-Brazil Merger. In that letter, R-CALF USA requested that your agency 1) oppose the JBS-Brazil Merger should evidence be found indicating any reduction in competition to either the U.S. cattle industry or the U.S. beef industry, 2) investigate the circumstances surrounding any anti-competitive practices alleged against and/or committed by JBS-Brazil, and 3) determine if U.S. laws are adequate and adequately enforced to prospectively prevent a recurrence of the kind and type of anti-competitive behavior as was alleged to have been perpetrated by JBS-Brazil. This communication is a follow-up to R-CALF USA's initial letter and describes in greater detail the basis for R-CALF USA's present request that the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) indefinitely block the JBS-Brazil Merger. As discussed below, R-CALF USA is concerned that the JBS-Brazil Merger would 1) harm the entire U.S. live cattle industry by reducing competition for slaughter-ready steers and heifers, resulting in reduced competition among and between the industry's subparts, and 2) harm U.S. live cattle producers by reducing competition in the U.S. live cattle market and subjecting them to abusive market power.

As a preliminary matter, R-CALF USA requests that the DOJ comport its analysis of the JBS-Brazil Merger to recognize the unique standing of the U.S. live cattle industry within the multi-segmented U.S. beef supply chain. The U.S. live cattle industry is a separate and distinct U.S. agricultural industry whereas the meatpacking firms subject to the horizontal merger aspect of the JBS-Brazil Merger – National and Smithfield – are manufacturing firms, recognized separately by the U.S. Department of Commerce as manufacturers of nondurable goods.1 Thus the cattle industry, a subset of the U.S. agricultural industry, is a distinguishable value-added, contributing industry to the gross domestic product of the United States; and the meatpacking industry, a subset of the food manufacturing industry, is itself a distinguishable value-added, contributing industry to the gross domestic product of the United States.2 These industry delineations are based on the 1997 North American Industry Classification System.3 The U.S. Census Bureau reinforces this industry delineation in its 2007 North American Industry Classification System ("NAICS") using a six-digit code.4 Under this system, "Animal Food Manufacturing" is a subset of "Food Manufacturing," which is a subset of the general industry type "Manufacturing."5 In contrast, "Cattle Feedlots" is a subset of "Cattle Farming and Ranching," which is a subset of the general industry type "Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting."6

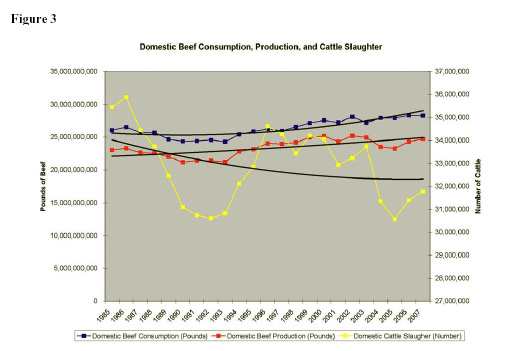

The delineation of the U.S. live cattle industry as a separate value-added industry is crucial to the DOJ's analysis of the JBS-Brazil Merger. If the DOJ mistakenly presumed the U.S. live cattle industry was not distinguishable as a separate industry, the mergers' potential impact on competition for slaughter-ready cattle (just one of the value-added products created within the U.S. cattle industry) would improperly be viewed as the ultimate outcome of the merger, and the likely impact from the merger would be significantly understated. This is because any lessening of competition, or exercise of market power in the slaughter-ready cattle market, would have a profound, though indirect impact on competition within the entire U.S. live cattle industry. For example, the competitiveness of the breeding stock industry is highly sensitive to market signals emanating from the slaughter-ready cattle market, e.g., supply-side signals indicating a need for herd expansion or liquidation, though this industry subpart does not generally market slaughter-ready cattle.7 To further explain this relationship, it is helpful to review the annual disposition and marketing of the varied products produced by the U.S. live cattle industry, i.e., the various classes of live cattle. In 2006 (latest comprehensive data available), total federally inspected cattle slaughter in the U.S. consisted of ~33 million head,8 which represented a total live weight of ~42 billion pounds, and generated a production value of ~$35 billion.9 However, in that year the U.S. live cattle industry actually marketed ~45 million head of cattle,10 which represented a total live weight of ~55 billion pounds, and generated cash receipts of ~$49 billion.11 What this data clearly shows is that the U.S. live cattle industry, a "Cattle Farming and Ranching Industry" depends only partially on the sale of slaughter-ready cattle to the "Food Manufacturing Industry" (hereafter "manufacturing industry") for its annual revenues. In fact, as evinced by this data, sales of live cattle not destined for sale to the manufacturing industry accounted for over 27 percent of the annual revenues generated by the U.S. live cattle industry in 2006.12

It is incumbent upon the DOJ to incorporate into its merger analysis the fact that there are two distinct subparts of the U.S. live cattle industry that would be affected by both the horizontal mergers and the vertical merger contemplated in the JBS-Brazil Merger. The first industry subpart includes cattle feedlots, which are primarily engaged in feeding of cattle for fattening and eventual sale to slaughter plants.13 As explained above, this subpart generated ~73 percent of the U.S. live cattle industry's revenues in 2006. The second subpart, which generated ~27 percent of industry revenues in 2006, and which does not generally sell products directly to slaughter plants, consists of a wide range of essential industry production activities including, but not limited to: beef cattle ranching or farming, backgrounding cattle, feeder calf production, stocker calf production, cattle conditioning operations, livestock breeding services, and showing of cattle, hogs, sheep, goats, and poultry.14 Though these significant U.S. live cattle industry subparts do not generally sell products directly to food manufacturers, they would nonetheless be impacted significantly by any lessening of competition or any exercise of market power by the manufacturing industry when live cattle are procured from cattle feedlots.

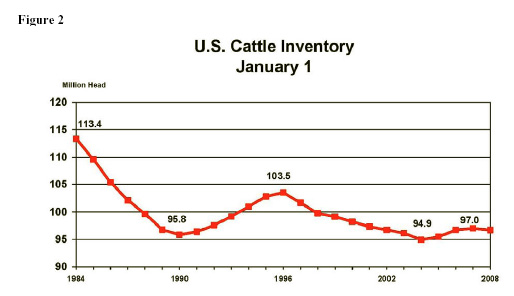

To understand how the significant, though non-feedlot subparts of the U.S. live cattle industry are impacted by changes in the level of competition occurring between cattle feedlots and the food manufacturing industry, it is helpful to consider the subpart of the industry that produces steers and heifers for slaughter, i.e., the largest subpart within the cattle feeding subpart, as the U.S. live cattle industry's flagship – its industry market maker. In 2006 the slaughter of steers and heifers accounted for the largest class of cattle slaughtered, totaling ~27 million head, or approximately 82 percent of the ~33 million cattle slaughtered that year.15 Those steers and heifers, with average carcass weights of 833 pounds and 767 pounds, respectively,16 produced ~22 billion pounds, or approximately 84 percent of the ~26 billion pounds of total beef produced in the U.S. in 2006 17 Because beef produced from steer and heifer slaughter is of high quality and constitutes a supermajority of all beef produced in the United States, it can be presumed that both the base price for beef and the base price for live cattle are intrinsically tied to the price of beef produced from steer and heifer slaughter. This presumption is validated by the fact that the expansion and contraction of the entire U.S. live cattle industry is intrinsically tied to the expected price of market weight cattle. The U.S. Government Accountability Office ("GAO") explained that the U.S. live cattle industry is subject to a historical cycle, referred to by "increases and decreases in herd size over time and [] determined by expected cattle prices and the time needed to breed, birth, and raise cattle to market weight," factors that are complicated by the fact that "[c]attle have the longest biological cycle of all meat animals."18

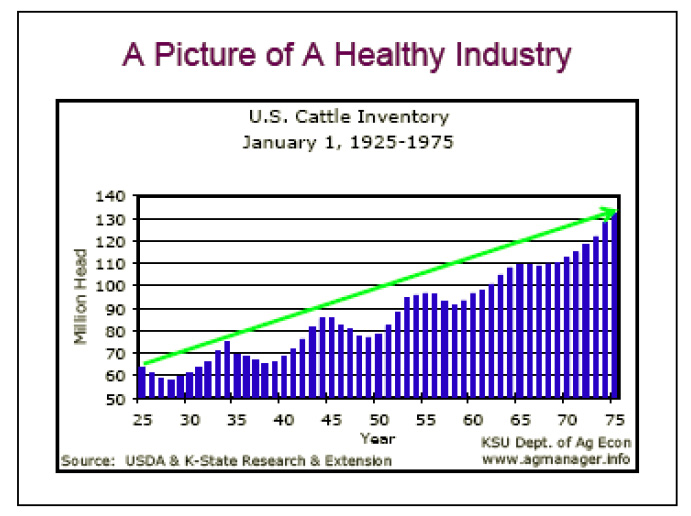

The U.S. cattle cycle historically occurred every 10-12 years, a function of the long biological cycle for cattle. The U.S. Department of Agriculture ("USDA") reported it consists of about 6 to 7 years of expanding cattle numbers, followed by 1 to 2 years in which cattle numbers are consolidated, leading to 3 to 4 years of declining numbers before the next expansion cycle begins again.19 In 2001, the USDA reported that the cycle has been shortened over time.20 However, in 2002 the USDA acknowledged that "the last cycle was 9 years in duration; the present cycle is in its thirteenth year, with two more liquidations likely."21 In early 2004 the USDA stated that 2003 marked the eighth year of herd liquidation in the current cattle cycle.22 In late 2005, the USDA declared that the U.S. was "in the early herd expansion stages of the new cattle cycle."23 In late September 2006, the USDA optimistically declared that the U.S. was "in the second year of expansion of the current cattle cycle."24 However, in late 2007, the USDA began cautioning the industry, stating that "[s]ome analysts suggest the cattle cycle has gone the way of the hog and dairy cow cycles."25 These analysts, according to the USDA, "suggested that the cattle cycle has returned to its liquidation phase."26 The foregoing discussion reveals that the historical U.S. cattle cycle began to function erratically during the last decade and continues doing so today, suggesting that the competition-induced demand/supply signals that once led to expectations about changes in cattle prices have been disrupted. While cattle industry analysts ponder this phenomenon, in February 2008 the USDA attributed a similar disruption that was occurring in the U.S. hog industry cycle to the hog industry's new structure. The USDA declared that the "New Hog Industry Structure Makes Hog Cycle Changes Difficult to Gauge," and stated, "The structure of the U.S. hog production industry has changed dramatically in the past 25 years."27 This "dramatically" changed structure includes the consolidation of the industry, where "fewer and larger operations account for an increasing share of total output."28 The USDA predicted that U.S. hog producers, which in January of 2008 were experiencing hog prices 17 percent below January 2007 prices, would likely be operating in the red in 2008.29 As was the case in the hog industry, a functioning cattle cycle, itself, is an indicator of a competitive market. The USDA succinctly explained: The cattle cycle refers to cyclical increases and decreases in the cattle herd over time, which arises because biological constraints prevent producers from instantly responding to price. In general, the cattle cycle is determined by the combined effects of cattle prices, the time needed to breed, birth, and raise cattle to market weight, and climatic conditions. If prices are expected to be high, producers slowly build up their herd size; if prices are expected to be low, producers draw down their herds.30 As the USDA explained with respect to the disrupted hog cycle, "In the past, persistent financial losses often prompted hog producers to liquidate breeding stock to reduce losses, or to exit the industry altogether."31 Obviously, such a liquidation of breeding stock previously resulted in a decrease in price-depressing hog supplies, which subsequently resulted in increased hog prices. Under the hog industry's new structure, however, the USDA claims it is now "difficult to predict the timing and duration of hog cycle changes."32 The recently acknowledged disruption of the historical U.S. cattle cycle, as discussed above, is a bellwether indicator that competition has lessened in the U.S. live cattle industry; and, as the USDA now succinctly concludes for the analogous hog industry cycle disruption, there is a causal relationship between this phenomenon and a changed industry structure marked by increased consolidation.

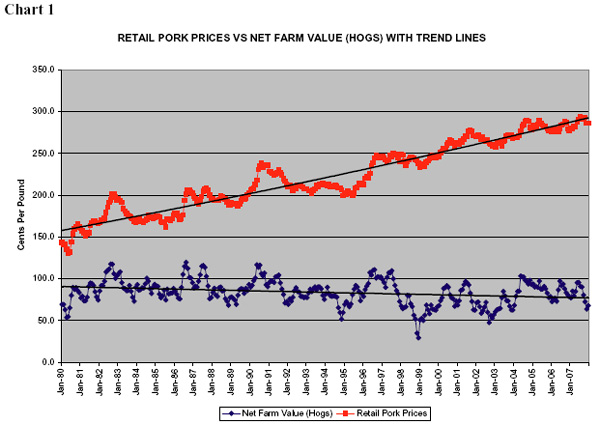

As shown in Chart 1 below, during the past 25-plus years, beginning January 1980, the new, more consolidated hog industry structure has resulted in a downward trend in live hog prices paid to producers and an upward trend in retail pork prices paid by consumers, along with an ever widening spread between farm prices and retail prices.

Data Source: USDA Economic Research Service.33

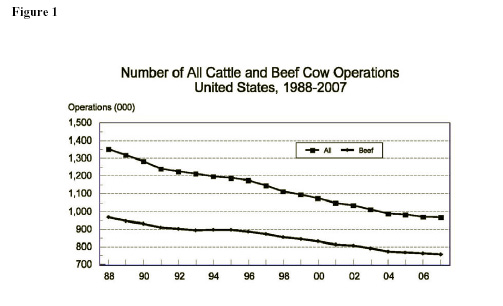

With respect to the U.S. live cattle industry as a whole, the relevant question the DOJ should ask when assessing the potential impacts of additional concentration in the beef manufacturing industry, as would occur under the JBS-Brazil Merger, is whether the merger would likely cause the U.S. live cattle industry to lose the critical mass of participants necessary to sustain current levels of competition that take place among and between its various subparts? Again, the U.S. live hog industry, once analogous to the U.S. live cattle industry in that it too sustained a vibrant industry consisting of hundreds of thousands of producers, has already experienced such a fait accompli. According to the USDA, during the period 1980 to 2004, when the concentration by the top four hog slaughter firms increased from 33.6 percent to 61.3 percent, the number of U.S. hog and pig operations declined from 667,000 in 1980 to only 67,000 by 2005.34 The U.S. live cattle industry also experienced an alarming contraction inverse to the increased concentration by the top four steer and heifer slaughter firms, which rose from 35.7 percent in 1980 to 81.1 percent in 2004.35 The size of the U.S. cattle industry, as measured by the number of cattle operation in the United States, declined from 1.6 million in 1980 to 983,000 in 2005.36 The DOJ must not ignore this inverse relationship, evinced by historical data, between increased concentration in the animal food manufacturing industry and marked decline in the size of the U.S. live cattle industry. Fortunately for the U.S. live cattle industry, there were significantly more U.S. cattle operations than U.S. hog and pig operations when the contraction of the two agricultural industries accelerated in 1980. With only 67,000 U.S. hog and pig operations remaining, the diminutive live hog industry lacks diversity and robust competition among and between its various subparts, with only 10 percent of its cash receipts generated from sales other than to food manufacturing industries.37 The U.S. live hog industry's present ability to contribute significantly to the gross domestic products of more than just a handful of states has also been reduced, with only 3 states generating gross incomes of more than $1 billion annually.38 In contrast, the U.S. live cattle industry, characterized by the remaining 983,000 cattle operations, still has the critical mass of participants necessary to generate significant revenues among and between its various subparts (as discussed above, 27 percent of the industry's cash receipts are from sales to buyers other than the food manufacturing industry). The U.S. cattle industry, despite its recent contraction, remains the single largest sector of U.S. agriculture, contributing approximately $50 billion annually to the U.S. economy,39 with significant economic contributions flowing to every state in the Union, including 11 states in which gross incomes from the sales of cattle exceeded $1 billion.40

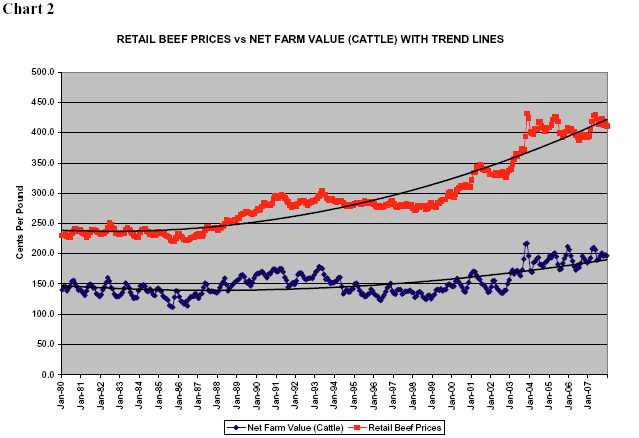

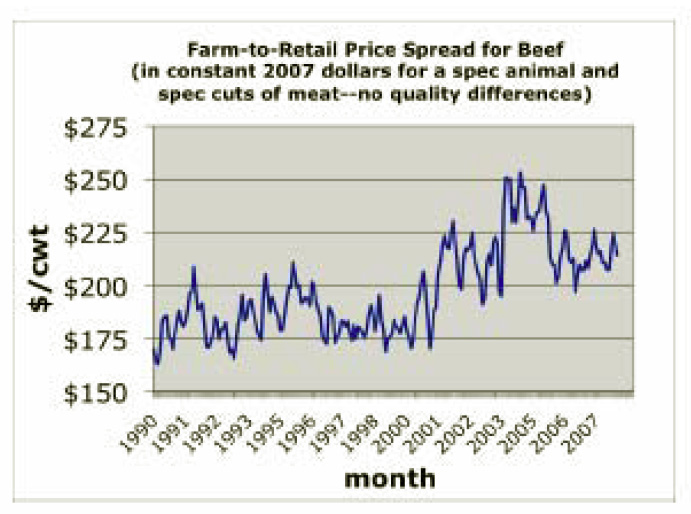

Chart 2 below reveals the relationship between retail beef prices paid by consumers and live cattle prices received by producers over the same 25-plus years that the cattle industry, like the hog industry, began its significant contraction. This is also the same period that the food manufacturing industry began its accelerated concentration. While the trend lines generally show that both retail beef prices and live cattle prices are synchronous and directed upward, thereby lacking the obvious inverse relationship present in the hog and pork prices depicted in Chart 1 above, the trend lines nevertheless show an obvious acceleration of the ever-widening gap between retail beef prices and cattle prices. This evidence suggests that there is an increased exercise of market power that enables the food manufacturing industry to extract a disproportionate profit from the sale of beef to consumers when compared to the share of the profits the cattle industry realizes when selling cattle to the food manufacturing industry.

Data Source: USDA Economic Research Service.41

Section I above described the structural-related concerns arising from the JBS-Brazil Merger that reveal the U.S. live cattle industry's inherent vulnerability to any further reduction in competition and any increase in market power or increased exercise of market power that would become manifest with increased consolidation of the existing structure of the animal food manufacturing industry. This section, Section II, will describe how the JBS-Brazil Merger would specifically create additional market power, and facilitate the exercise of that additional market power upon the U.S. steer and heifer market, which, as described in Section I above, is the portal through which the harmful effects of market power would endanger the entire U.S. live cattle industry. The harm that would accrue directly to U.S. steer and heifer producers as a result of the JBS-Brazil Merger is the harm arising from the exercise of market power by buyers ("monopsony power"). R-CALF USA will demonstrate that an assessment of R-CALF USA's monopsony concerns arising from the JBS-Brazil Merger, when applied to the analytical framework analogous to the DOJ's Horizontal Merger Guidelines ("Guidelines"), reveals the imminent harm that would accrue to the U.S. live cattle industry unless the JBS-Brazil Merger is indefinitely blocked.42 This harm would be the result of the JBS-Brazil Merger's creation and enhancement of monopsony power and the facilitation of its exercise.43

As revealed by Chart 3 below, the JBS-Brazil Merger would significantly increase the capacity concentration in the U.S. steer and heifer slaughter by changing the current four-firm capacity concentration, which USDA estimates at 79.1 percent,44 to an estimated four-firm capacity concentration of approximately 91.2 percent.45 This estimate represents a 12.1 percent increase in capacity concentration as a result of a 33 percent decrease in the number of firms that would compete for this 91.2 percent share of the market, with the number of competing firms shrinking from 6 to 4.46 Chart 3

Pre-Merger USDA estimate of Four-Firm Capacity Concentration:79.1%**** Notes: * AMI data are attached as Exhibit 2. Though R-CALF USA does not venture an estimate of the increased Herfindahl-Hirschman Index ("HHI") that would result from the JBS-Brazil Merger, the CME Group did and estimated the increase to be dramatic, growing by 638 points.47

Although the USDA data discussed in Section I suggests that the contraction of the U.S. live hog industry was more severe than was experienced by the U.S. live cattle industry, despite a smaller four-firm concentration ratio of the pork manufacturing industry, there is a measurable difference in the degree to which the concentrated pork manufacturing industry was able to exercise its inherent market power. For example, the pork manufacturing industry exploited the live hog industry's greater propensity toward vertical integration of the entire live hog production cycle – from birth to slaughter – and captured earlier in the industry's concentration process a larger proportion of slaughter-ready hogs before they entered the open cash market, where the base-price for all hogs marketed continues to be established. The recently completed GIPSA Livestock and Meat Marketing Study ("LMMS") found that during the period October 2002 through March 2005, the pork manufacturing industry captured 20 percent of its slaughter-ready hogs through the alternative procurement method of direct ownership;48 about 57 percent of hogs were captured through marketing contracts, forward contracts or marketing agreements; and fewer than 9 percent of hogs were procured in the open market.49 Among the conclusions of the LMMS was: "Based on tests of market power for the pork industry, we found a statistically significant presence of market power in live hog procurement."50 Further, the LMMS concluded that there was a casual relationship between the increased use of non-cash hog procurement methods and lower prices for hogs: Of particular interest for this study is the effect of both contract and packer-owned hog supplies on spot market prices; as anticipated, these effects are negative and indicate that an increase in either contract or packer-owned hog sales decreases the spot price for hogs. Specifically, the estimated elasticities of industry derived demand indicate - a 1% increase in contract hog quantities causes the spot market price to decrease by 0.88%, and - a 1% increase in packer-owned hog quantities causes the spot market price to decrease by 0.28%. A higher quantity of either contract or packer-owned hogs available for sale lowers the prices of contract or packer-owned hogs and induces packers to purchase more of the now relatively less expensive hogs and purchase fewer hogs sold on the spot market.51 The LMMS found that procurement methods that facilitated the exercise of market power by the concentrated pork manufacturing industry are currently less developed by the concentrated beef manufacturing industry. For example, the study found that only 5 percent of live cattle were procured through packer-ownership and only 33.3 percent of cattle were procured by forward contracts and marketing agreements, leaving nearly 62 percent of the cattle procured through the open market,52 which continues to set the base price for all marketed cattle. Although alternative procurement methods for cattle destined for slaughter are currently less developed than for hogs destined for slaughter, the LMMS nonetheless found a causal relationship between the increased use of alternative slaughter-ready cattle procurement methods and a decrease in the cash market price for slaughter-ready cattle under the current structure of the beef manufacturing industry. The LMMS found that a 10 percent shift of the volume of cattle procured in the open market to any one of the alternative procurement methods is associated with a 0.11 percent decrease in the cash market price.53

Chart 4 below lists the plant locations for each of the five largest beef-related food manufacturers: Chart 4

While it appears that the beef manufacturing industries subject to the JBS-Brazil Merger do not presently compete against each other in any of the states where their plants currently exist, this measure of competition is irrelevant in the U.S. live cattle industry. This is because the market for both feeder cattle and fed cattle is more national in scope. This appears also to be the case for the wholesale beef market. According to a recent study by John R. Schroeter, "The wholesale beef market . . . is essentially national in scope and insulated, to some extent, from the vagaries of the terms and volume of trade in a single regional fed cattle market."59 Further, a study by Mingxia Zhang and Richard J. Sexton reported that a number of researchers argue "based on a variety of empirical tests, that regional cattle prices are closely interrelated and that 'analyses of concentration in beef packing need to focus on relatively broad geographic markets.'"60 Importantly, the researchers presented a general view that regional competition for raw products, which would include live cattle, is inherently less intense than is competition in processed food products.61 Based on this finding, the DOJ should conduct its review of the JBS-Brazil Merger with the understanding that competition for slaughter-ready cattle is inherently fragile, even without the added burden of monopsony power. And, as such, the market for slaughter-ready cattle should be accorded even greater protections than would be accorded to markets for processed food products.

Producers of fed steers and heifers are subject to "market access risk," which refers to "the availability of a timely and appropriate market outlet."62 This risk is particularly significant because fed cattle are perishable commodities that must be sold within a fairly narrow time frame, otherwise they will decrease in value.63 Under the current level of beef manufacturing industry concentration, there is already evidence that producers of steers and heifers are subjected to market power and are foregoing revenues to avoid market access risk. The LMMS found that "[t]ransaction prices associated with forward contract transactions are the lowest among all the procurement methods [including cash market procurement methods],"64 and proffered that the results of the study may suggest that "farmers who choose forward contracts are willing to give up some revenue in order to secure market access . . ."65 The JBS-Merger would exacerbate market access risk for steer and heifer producers by effectively shrinking the number of market outlet gatekeepers for the estimated 92.1 percent of market outlet capacity from six firms to only four firms, as was previously discussed above.

While the beef manufacturing industry has been limiting the number of its market outlet gatekeepers through horizontal consolidation, thus creating market access risk for cattle producers, the beef manufacturing industry has been simultaneously increasing its use of non-traditional contracting and marketing methods, enabling it to more effectively exercise its manifest market power. These non-traditional cattle procurement methods increase the vertical coordination between the live cattle industry and the beef manufacturing industry and include purchasing cattle more than 14 days before slaughter (packer-fed cattle), forward contracts, and exclusive marketing and purchasing agreements. Together, the four largest beef manufacturers employed such forms of "captive supply" contracting methods for a full 44.4 percent of all the cattle they slaughtered in 2002.66 And use of these captive supply methods has been increasing rapidly, rising 37 percent from 1999 to 2002.67 As stated above, the LMMS found that approximately 38 percent of cattle were procured by such non-traditional methods during the period October 2002 through March 2005. Captive supplies have been shown to increase the instability of prices for cattle producers and hold down cattle prices.68 Over the past 20 years studies have supported the idea that buyer concentration in cattle markets systematically suppressed prices, with price declines found to range from 0.5 percent to 3.4 percent.69 As average prices for cattle are artificially depressed and become more volatile, due to these captive supply procurement methods, it is cattle producers who pay the price, even when broader demand and supply trends should be increasing returns to producers.70 Despite this negative outcome, cattle producers continue to opt into captive supply arrangements because those producers have few other attractive marketing choices in an industry that effectively reduces access to market outlets.71 Furthermore, while such captive supply arrangements may appear attractive to an individual producer at a given point in time, the collective impact of these contracting practices on the market as a whole is harmful to the live cattle industry. Producers acting individually are not in the position to change these dynamics of the market. The JBS-Brazil Merger would facilitate the exercise of market power by further concentrating control over market access, thus increasing the propensity for live cattle producers to continually enter captive supply arrangements despite their negative impact on the live cattle industry.

The beef manufacturing industry recently exacted its market power on the U.S. cattle industry for purposes of influencing national public policy; and, in doing so, imposed unnecessary costs and burdens on U.S. cattle producers, which costs and burdens U.S. producers could not avoid without eliminating or severely limiting their marketing options. In March 2003, beef-related food manufacturer IBP, Inc., notified U.S. cattle producers that it would require producers to, inter alia, "Provide IBP, inc. access to your [producers'] records so that we [IBP] can perform random producer audits . . ." and "Provide third-party verified documentation of where the livestock we [IBP] purchase from you [producers] were born and raised.72 This coercive threat to impose costly and burdensome requirements on U.S. cattle producers was initiated by IBP for the express purpose of soliciting producers' help in contacting "Senators or members of Congress," to whom producers were asked to express their concerns regarding IBP's plans to impose such onerous conditions on their industry. This was IBP's political response to Congress' passage of the mandatory country of origin labeling law.73 This abuse of market power was initiated months before the USDA even published its October 30, 2003 proposed rule to implement the country of origin labeling law. Such abuses of market power would be facilitated by the JBS-Brazil Merger as U.S. cattle producers' market outlets would become even more limited, particularly in certain geographic areas, and producers would not be able to avoid the arbitrary dictates of any one of the remaining beef manufacturing industries.

In addition to the application of price premiums and discounts for contract or grid-priced cattle that are based on standardized USDA yield and quality grades, Tyson and Smithfield have each established different price premiums and discounts for additional factors, such as muscle scoring. For example, Smithfield discounts certain muscle scores between $5.00 per cwt. and $10.00 per cwt, and Tyson uses muscle scores to apply varying discounts under a different system.74 These discounts and premiums are purported to reflect consumer preferences,75 but whether a $120 discount (i.e., $10 per cwt. applied to a 1,200 lb. animal) is reflective of the actual discount the beef manufacturing industry receives upon the sale of the resulting meat, or if it represents a windfall for the beef manufacturing industry, is undeterminable without additional information. Nevertheless, the ability to impose such discounts, without knowing if they are legitimate, is facilitated by the currently limited marketing outlets, which would become even more limited under the JBS-Brazil Merger. There is a host of potential market power abuses, the propensity toward which would be facilitated by an increased concentration of the steer and heifer market, that would either force producers into compliance or cause them to suffer economic losses. For example: a beef manufacturer in a more concentrated market could establish discounts for cattle that were not conceived by the beef manufacturer's preferred genetic lineage, or that were not fed the beef manufacturer's preferred brand of mineral or feed supplement. Thus, the potential for the beef manufacturing industry to impose wholly arbitrary product specifications, which directly result in lower cattle prices paid to producers, is a significant concern arising from the JBS-Brazil Merger.

As part of its investigation, the DOJ should determine if pricing strategies of the concentrated beef manufacturers, such as that described in the example above, are among the reasons for the pricing anomalies disclosed in the LMMS study. The LMMS study states that in direct trade transactions based on a carcass weight valuation, the average cattle price is 1.3 cents lower than the average price for direct trade transactions with live weight valuation.76 Even more striking is the difference for grid valuation transactions, where prices average 1.8 cents lower than the average price for direct trade transactions.77 Assuming an average dressed weight for cattle of 781 pounds,78 this price differential translates into a loss of $10.15/head for producers selling on a carcass weight basis and a loss of $14.06/head for producers selling on a cash grid basis compared to producers selling on a live weight valuation. It is important to note that these comparisons hold other explanatory variables for price differentials fixed in the model.79 When this price difference is multiplied times the volume of cattle sold during the period examined by the LMMS study, it adds up to a total loss of $202,631,068 for producers who sold their cattle on the cash market on a carcass weight or grid basis rather than a live weight basis.80 The LMMS study reveals that cattle producers selling their animals on a carcass weight basis or a grid basis have lost more than $200 million on these transactions in the period covered by the study. The anomalous price differential for dressed weight and grid basis cattle compared to cattle sold on a live weight basis appears counter-intuitive and contradicts a conclusion that beef manufacturers use purchasing methods that provide an incentive for quality and yield. Instead, it appears that the uncertainty inherent in dressed weight and grid basis transactions, and the transference of that price risk from beef manufacturers to cattle producers through these types of transactions, has only operated to depress prices for live cattle and to deprive cattle producers of a market-based price for their product. The data suggest that beef manufacturers have been able to manipulate the grid system to engineer a lower overall average return to producers who sell on a grid basis. This practice fails to send the right market signals to producers and feeders, and it creates a counter-intuitive disincentive to sell on a grid basis and to seek premiums for yield and quality characteristics. The LMMS data reveal an unreasonable and unfair depression of cattle prices for those producers who sell on a grid basis that is contrary to competitive market fundamentals.

Tyson Fresh Meats, Inc., ("Tyson") has issued presumably new terms and conditions under which it will purchase cattle for slaughter.81 Tyson states that it "does not typically accept for processing at its facilities" cattle that exceed 58 inches in height, cattle that exceed 1,500 pounds, or cattle with horns longer than 6 inches in length.82 The imposition of such restrictions presents a number of competition-related concerns: First, if Tyson is one of only two buyers in the marketing region where such restricted cattle are potentially available (i.e., cattle are approaching but have not yet exceeded any of Tyson's restrictions) and if the other buyer imposed no comparable restrictions, then the other buyer would have an incentive not to bid on such cattle, which, if Tyson did not purchase, would be available for sale at a discount as soon as Tyson's restrictions were exceeded. In fact, Tyson would have an incentive to lowball such potentially available cattle knowing that if the producer did not sell to Tyson within a short period of time, there would be no competition for the cattle after the restrictions were exceeded. Second, for cattle that already exceed Tyson's restrictions, regardless of the demand for beef, the producer would have significantly fewer market outlets for the cattle. Third, this action constitutes an outright denial of access to the marketplace, which is even more egregious than would be a discount for cattle that exceeded Tyson's restrictions, as it automatically eliminates a dominant competitor from the marketplace. The JBS-Brazil Merger would potentially exacerbate the division of the marketplace that has already been initiated by Tyson. Should one beef manufacturer declare that it would slaughter only steers, only heifers, only Holsteins, or only hornless cattle, for example, the marketplace could be sufficiently divided by the remaining food manufacturers to severely limit competition for each subclass of cattle, if not eliminate competition altogether.

Under the existing, concentrated structure of the beef manufacturing industry, empirical evidence shows that the U.S. cattle market is already susceptible to coordinated and/or simultaneous entries and exits from the market. In February 2006, all four major beef-related food manufacturers – Tyson, Cargill, Swift, and National – withdrew from the cash cattle market in the Southern Plains for an unprecedented period of two weeks. On February 13, 2006, market analysts reported that no cattle had sold in Kansas or Texas in the previous week.83 No cash trade occurred on the southern plains through Thursday of the next week, marking, as one trade publication noted, "one of the few times in recent memory when the region sold no cattle in a non-holiday week."84 Market analysts noted that "[n]o sales for the second week in a row would be unprecedented in the modern history of the market."85 During the week of February 13 through 17, there were no significant trades in Kansas, western Oklahoma, and Texas for the second week in a row.86 Market reports indicated that Friday, February 17, 2006, marked two full weeks in which there had been very light to non-existent trading in the cash market, with many feedlots in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas reporting no bids at all for the past week.87 The beef manufacturers made minimal to no purchases on the cash market, relying on captive supplies of cattle to keep their plants running for two weeks and cutting production rather than participating in the cash market. The beef manufacturers reduced slaughter rates rather than enter the cash market. Cattle slaughter for the week of February 13 – 17 was just 526,000 head, down from 585,000 the previous week and 571,000 at the same time a year earlier.88 According to one analyst, the decision to cut slaughter volume indicated "the determination by beef packers to regain control of their portion of the beef price pipeline."89 Another trade publication noted that the dramatic drop in slaughter was undertaken in part to "try and get cattle bought cheaper."90 At the end of the second week of the buyers' abandonment of the cash market, one market news service reported, "The big question was whether one major [packer] would break ranks and offer higher money. That has often occurred in the past, said analysts."91 As a result of the beef manufacturers shunning the cash market, cash prices fell for fed cattle, replacement cattle, and in futures markets. Sales took place after feedlots in Kansas and the Texas Panhandle lowered their prices to $89 per hundredweight, down $3 from the $92 per hundredweight price reported in the beginning of February.92 The same day, February 17, live and feeder cattle futures fell to multi-month lows.93 Replacement cattle prices also dropped in response to buyer reluctance.94 In Oklahoma City, prices for feeder cattle dropped as much as $4 per hundredweight.95 Whether the beef manufacturers' simultaneous boycott of the cash market was deliberately coordinated or not, it was a highly unusual event that required simultaneous action in order to effectively drive down prices, which it did. As market analysts observed, the major question in markets during the second week of the buyers' strike was whether or not any one of the major beef manufacturers would "break ranks" to purchase at higher prices than the other beef manufacturers. No buyer did so until prices began to fall. In fact, beef manufacturers were willing to cut production rather than break ranks and purchase on the cash market. Abandonment of the cash market in the Southern Plains by all major beef manufacturers for two weeks in a row resulted in lower prices and had an adverse effect on competition. Cattle producers in the Southern Plains cash markets during those two weeks were unable to sell their product until prices fell to a level that the buyers would finally accept. The simultaneous refusal to engage in the market did not just have an adverse effect on competition – it effectively precluded competition altogether by closing down an important market for sellers. The simultaneous boycott of cash markets in the Southern Plains was, however, a business decision on the part of the beef manufacturers that did not conform to normal business practices and that resulted in a marked decline in cattle prices. At the time, market analysts interpreted the refusal to participate in the cash market as a strategy to drive down prices, and purchases only resumed once prices began to fall. The coordinated/simultaneous action in February 2006 was not isolated and was soon followed by a second, coordinated/simultaneous action. During the week that ended October 13, 2006, three of the nation's four largest beef manufacturers – Tyson, Swift, and National -announced simultaneously that they would all reduce cattle slaughter, with some citing, inter alia, high cattle prices and tight cattle supplies as the reason for their cutback.96 During that week, the packers reportedly slaughtered an estimated 10,000 fewer cattle than the previous week, but 16,000 more cattle than they did the year before.97 Fed cattle prices still fell $2 per hundredweight to $3 per hundredweight and feeder prices fell $3 per hundredweight to $10 per hundredweight.98 By Friday of the next week, October 20, 2006, the beef manufacturers reportedly slaughtered 14,000 more cattle than they did the week before and 18,000 more cattle than the year before – indicating they did not cut back slaughter like they said they would.99 Nevertheless, live cattle prices kept falling, with fed cattle prices down another $1 per hundredweight to $2 per hundredweight and feeder cattle prices were down another $4 per hundredweight to $8 per hundredweight.100 The anticompetitive behavior exhibited by the beef-related food manufacturers' coordinated/simultaneous market actions caused severe reductions to U.S. live cattle prices on at least two occasions in 2006. This demonstrates that the exercise of market power is already manifested in the U.S. cattle industry – a situation that would only worsen if there were even fewer buyers in the marketplace. For example, the reduction in cattle prices that followed the coordinated/simultaneous actions of four beef-related food manufacturers in February 2006 and three beef-related food manufacturers in October 2006 could be accomplished by only three beef manufacturers, and only two beef manufacturers, respectively, should the JBS-Brazil Merger be consummated. The potential for a recurrence of this type of anticompetitive behavior is considerable and constitutes an empirically demonstrated risk that would likely become more frequent, more intense, as well as extended in duration. Therefore, this anticompetitive behavior is evidence that the JBS-Brazil Merger would reduce competition in the marketplace.

On November 28, 2007, Dow Jones Newswires reported that "JBS SA's Friboi Group (JBSS3.BR)" was among a number of Brazilian companies which, after a two-year investigation by the Brazilian Justice Department's antitrust division, were accused of engaging in anticompetitive practices.101 JBS SA was reportedly charged with "anti-competitive practices for coordinating price agreements among themselves in order to keep cattle prices low when purchasing livestock for slaughter."102 The report indicated that JBS SA had denied the charges. However, in a subsequent news article, JBS SA reportedly agreed to pay $8.5 million to an antitrust fund as a result of the charges and further agreed to end the practices that were allegedly anti-competitive.103 This example demonstrates that it is highly likely that the U.S. live cattle market would be subjected to coordinated interaction by JBS-Brazil given that the company was reportedly accused, and was found culpable based on the payment of restitution, of engaging in such anticompetitive behavior in another geographic market, which is comparable to the U.S. market.

If consummated, the JBS-Brazil Merger would result in the nation's largest beef manufacturer owning Five Rivers, the nation's largest cattle feeding company. Five Rivers currently feed and market approximately 2 million cattle annually and is currently owned by the nation's fifth largest beef manufacturer, Smithfield, under a joint venture.104 Based on Smithfield's estimated daily capacity of 7,975 cattle (see Chart 3), and applying the 260 reporting days established by the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service ("AMS") as the number of annual slaughter days,105 Smithfield's estimated annual slaughter is 2.1 million. Therefore, Smithfield's ownership of Five Rivers gives it sufficient numbers of fed cattle to meet nearly 100 percent of its annual slaughter capacity. However, it is not likely that Smithfield could coordinate the finishing of cattle such that it could meet its daily capacity throughout the year with cattle from its own feedlots. If this assumption is correct, Smithfield would likely have fewer cattle than it needs on a daily basis during some periods, in which case it would need to purchase from other sources, thus adding to the competitiveness of the market. And, it would likely have more cattle than it needs on a daily basis during other periods, in which case it would need to sell cattle to other beef manufacturers, thus again adding to the competitiveness of the market. Post-merger, JBS-Brazil would own both Smithfield and Five Rivers, affording it control over approximately 2 million fed cattle annually, representing approximately 7 percent of the nation's annual steer and heifer slaughter. However, whereas Smithfield was not likely capable of slaughtering 100 percent of the cattle fed at Five Rivers, due to the combination of limited daily slaughter and the logistics of timing the finishing of cattle, thus potentially contributing to the market volume of cattle sold to other beef manufacturers, JBS-Brazil could likely slaughter all of the cattle fed at Five Rivers due to its significantly increased number of plants and capacity. The effect would be a potential increase in the percentage of packer-owned cattle presently slaughtered on a national basis and a potential reduction in the volume of cattle sold in the cash market – a circumstance that would effectively thin the cash market and potentially drive down prices. The DOJ should investigate both the current practices of Smithfield with respect to the disposition of cattle fed at Five Rivers and the change in this disposition of cattle that would likely occur should the JBS-Brazil Merger be consummated.

Congress enacted the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921 ("PSA") to not only prohibit anticompetitive and monopolistic practices, but also to protect livestock producers from unfair, deceptive, and manipulative practices by the animal food manufacturing industry. Thus, the PSA goes well beyond the traditional antitrust concerns of efficiency and market competition. The PSA's central provision for protecting the U.S. live cattle industry is 7 USC § 192. Section 192 provides: It shall be unlawful for any packer or swine contractor with respect to livestock, meats, meat food products, or livestock products in unmanufactured form, or for any live poultry dealer with respect to live poultry, to: